Lost in the Light: How I Re-discovered Wonder

Three Generations, Two Telescopes, and One Infinite Sky

The first time I saw Orion's Belt, I was nine years old, lying on our family terrace in India. The concrete floor still held the day's warmth beneath my wooden cot, and the night air carried the sweet scent of flowers from my grandmother’s terrace garden. We didn't have air conditioning, so my family and I would sleep outside under the canopy of stars on most nights when weather allowed.

The terrace became my bedroom and my first observatory. Dad and I would lie side by side, my Dad's finger traced the three perfect stars in the night sky, then moved upward using a handheld telescope and pointed to an object glowing red like a distant ember. "That star," he told me, "is so large it could swallow a thousand suns." I stayed awake late into the night wondering about the vastness of it all, my mind exploding with questions: What do we know about these distant stars? Where do this stars go during daytime? Why can we only see them at night?

The Nature of Wonder

Wonder has this infinite vastness of possibilities which feels like opening doors in my mind that I didn't know existed. It's pure and unconditional quality, requiring no special equipment, no expensive tickets, and no years of study. Just a willingness to look up and let my mind roam free in the landscape of curiosity. It was in those moments of mystery and imagining, I experienced something profoundly human: the innate desire to understand our place in the mysterious sea of stars.

"The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science." - Albert Einstein

This is what I gradually lost touch with in the past few decades, not just the stars themselves, but that state of pure, unbound curiosity. That feeling of standing at the edge of infinite possibility, where a question leads to more questions, and each answer reveals new mysteries to explore.

A Lost Connection

That nine year old astronomer would be disappointed in me now, knowing how my gaze gradually shifted downward, eyes on the next deadline, the next opportunity, the next milestone. Always looking forward to what’s next, but never up. Somewhere between college applications and career ladders, I forgot about the vast layers of space I wanted to get lost into every night as a child. My relationship with the cosmos gradually reduced to occasional glances at astronomy posts on my phone, usually before going to bed or waiting in the lines at the grocery store. The stars continued broadcasting their ancient stories, but I had gotten lost in the static of my own stories.

Those nights on the terrace had etched themselves into my consciousness, carving pathways that would guide me back decades later. Growing up I could look at part of the sky and knew where I would find my favorite constellations, but sometime in adulthood the map of my mind had so many dead ends that I get lost in the dark skies when looking for the Big Dipper or Orion’s Belt. Ironically, we're also living in the golden age of cosmic discovery, where my smartphone can name every star in the sky and give me the latest updates on the discovery of new zip codes in our universe.

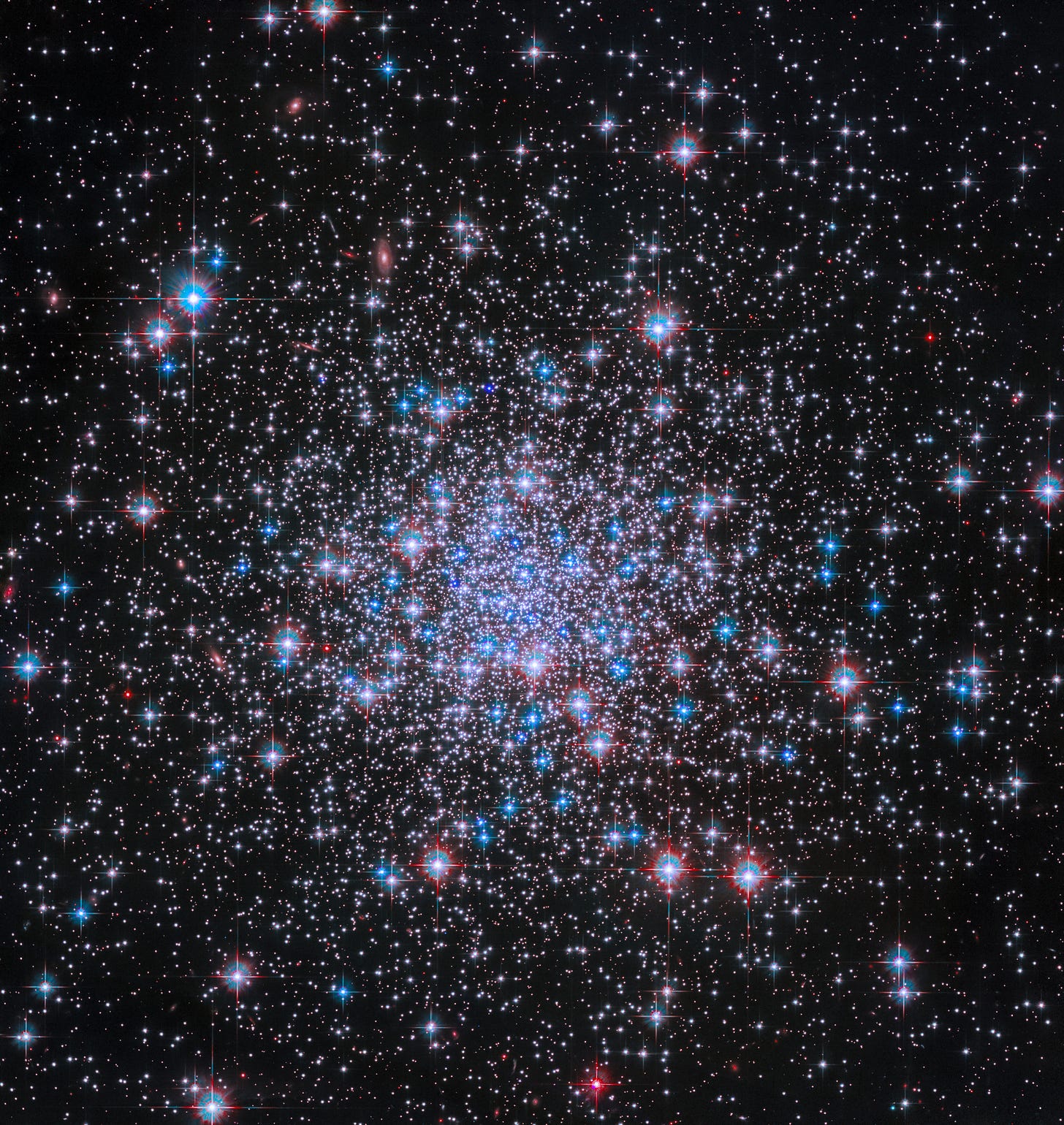

I remember the first time I saw an image of NGC 2298 - a sparkling collection of stars held together by gravitational attraction. I was browsing through my Bluesky feed and before I could finish reading the sentence of the image taken by the Hubble telescope, I felt this nostalgic feeling of wonder and the memory brought me right back to those nights on that terrace in India. The celestial marvel (NGC 2298) hangs in space like a forgotten jewel, its hundreds of thousands of stars bound by intermediate-mass black holes.

The light we see today from this part of the Milky Way began its journey more than 160,000 years ago toward Earth, when our ancestors were crafting their first stone tools. Today, we can capture this ancient light with instruments made of thousands of gold-plated mirrors and sensors that can detect the faintest flicker of light from deep space. Though separated by millennia, both tools served the same timeless human desire: to explore the stellar unknown. The image speaks of something deeper than mere scientific discovery, it reminds us of humans' fundamental connection to the cosmos.

The Fading of the Stars

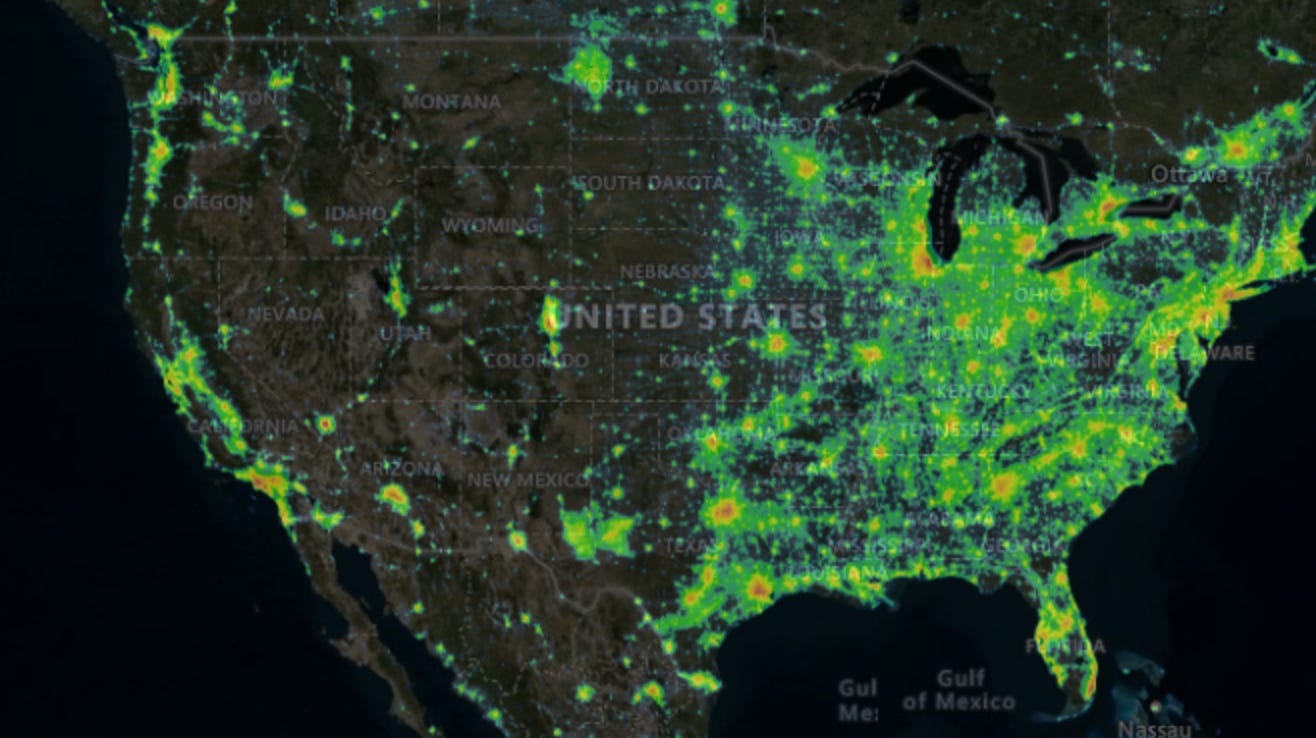

Last summer, I took my son camping, eager to show him the constellations I once knew by heart. But standing there under the open sky, I couldn't find Orion's Belt, those three perfect stars that had once been as familiar as my own home. The few visible stars seemed to mock my forgotten skill. Later, I was reminded by the internet scientists that we, like 80% of Americans, live under skies so light-polluted that these constellations have become invisible to an entire generation.

Our ancestors relied on these same stars for survival, using them as GPS to navigate vast oceans, as calendars to time their harvests, and as clocks to mark the passage of time. Yet here we were, in the process of losing this ancient connection. We've found a way to light the earth at night and in the process, we have stolen the stars from ourselves.

Finding Dark Skies

It started with a chance encounter at our local library. My son spotted a telescope available for borrowing—something I didn't even know libraries offered. "Can we take it home, Papa?" he asked, his eyes bright with the same curiosity I once felt about telescopes.

Later in the week on a crisp fall evening, we pointed our wobbly telescope at the moon. "Papa, I see some volcanoes!" my son shouted, his breath fogging in the cold air. "Those are craters," I explained, suddenly remembering my own childhood confusion. We adjusted the focus on the telescope and the moon's surface came into sharper view: the jagged edges of the large crater casting long shadows, and the bright rays of another crater stretching across the lunar landscape. Each new image from the telescope sparked a new question from him, just as they had from me when my Dad would point out the moon’s landscape, patiently explaining each one while cricket songs broke the evening’s silence.

That borrowed telescope sparked something in us. We began planning camping trips to dark sky sites, as far from city lights as possible. Last August, we drove four hours into the wilderness of Middle Fork River Forest Preserve. As night fell and our campfire dimmed to embers, the sky transformed. Without the city's artificial glow, thousands of stars emerged from hiding. My son had never seen such spectacle of nature, he said, "Papa, it looks like glitter!" with excitement, spinning in circles trying to take it all in. For the first time, he was experiencing what I had witnessed as a child: not only scattered points of light, but a vast cosmic playground.

These camping trips have become an annual ritual, resembling those nights on the terrace with my Dad. My son now quizzes me about the constellations, just as I once use to with my father. Sometimes I know the answers, sometimes I don't, but in those moments of discovery, generations of stargazers seem to bond beneath the same eternal sky. In times where we can hold the entire cosmos in our smartphones, the wonder remains the same: a father and child, connected by curiosity, asking questions that reach across time.

Now when my son and I are looking at stars from our apartment’s balcony - our own version of that old terrace in India. The street lights dim most stars, but Orion's Belt cuts through the haze, as brilliant as it was on that first night my father showed it to me. My son's finger traces the three stars, just as mine once did, just as countless fingers have done across millennia. The concrete beneath us might be different, the sky might be dimmer, but that wonder still burns bright—passed down like starlight, from father to son to grandson, each generation adding its own stories about the infinite mystery we are part of. In the end, perhaps that's what the stars have always been: not just distant suns, but bridges across time, connecting us to our past, our future, and to each other.

Infinite gratitude to the brilliant editors who helped guide this piece home. Their thoughtful questions and insights helped me focus on the stories that really mattered.

Thank you

, , , , .

Lovely story about reconnecting with curiosity through generations :) I like that you end on being able to trace Orion's belt again! Only a temporary loss while you built foundations elsewhere, is how I like to view it

Also, that map of the US light pollution was so interesting to see - the Western part of the map is so blank/clear compared to the Eastern half. Fascinating.

Amit, can't really express well how much I appreciate this type of article in the sea of distraction and information overload that makes up our modern world. Growing up in the US Southwest we had amazing skies. I'll never forget a camping trip in Moab, Utah and looking up at the stars. It's a memory that still fuels me with wonder decades later. Thinking of the cosmos, and seeing the photos that new telescopes take, really puts things in perspective for me. It's fabulous to be linked by these experiences, you on your porch on hot nights in India and me in rural Colorado. We can find and focus on these human connections to each other if we try, and how beautiful that it's the stars, which we're physically made of, that can make them possible.