The Measure of a Breath

How Do You Heal a Part Without Seeing the Whole?

I'm watching dad count his breaths, because when breathing becomes work, you start measuring it. His chest rises and falls with deliberate effort, each inhale a small victory against the fluid that had been slowly drowning his lungs from the inside.

Three days earlier, he told me he was having trouble breathing. He couldn't catch his breath when he woke up at night to and back from the bathroom. When you're 79 with diabetes, high blood pressure, and a heart that beats to its own irregular rhythm, shortness of breath is alarming.

The chest X-ray revealed what the doctors called "concerning fluid build-up" around his lungs, pressing against his heart. His primary care physician, reviewing the results while traveling, didn't mince words: "Get him to the ER. ASAP."

What followed was eight days that laid bare everything that's both miraculous and maddening about our healthcare system.

The Daily Dance

Every day, the same routine unfolded. Different doctors enter dad's room at different times to check on Dad. Each brilliant in their domain, each seeing their piece of the puzzle with laser focus.

When I'd ask about discharge plans or how his conditions connected, I'd get medical ping-pong: "Talk to cardiology about that." "You'll need to check with pulmonology." "The other doctor will decide."

After four days of this medical hot potato game, where dad apparently belonged to everyone and no one, I couldn't wait any longer, so I made my request clear to both specialists. I said, "I need you two to actually talk to each other and give us a unified answer."

The Questions Building

Dad had lost significant weight over the past two years. We still don't know why after doing every test imaginable that were recommended by his medical team. He has atrial fibrillation that affects his heart rhythm. He takes multiple medications that interact in ways that would make a pharmacist's head spin. He's dealing with the accumulated stress of aging, of watching his body become less reliable.

How do these pieces connect? How might his dramatic weight loss relate to the fluid build-up? Could his medications be contributing? What about his diet, his activity level, the complex interplay of his chronic conditions?

These questions kept circling through my mind, but they weren't the ones anyone was asking. Instead, I watched doctors pattern-match—efficient, yes, but not particularly curious about what made Dad's case unique. We got more of what worked for similar cases rather than what this particular person might need. When I asked what we can do to prevent this from happening again, I got vague redirects: “That's really more of a primary care question.”

The System's Blind Spots

I felt torn. Grateful that Dad was getting the care he needed, yes. But also frustrated that we kept missing opportunities to see him as more than a collection of symptoms. The system was saving his life while somehow losing sight of the person living it.

Instead, we get symptom whack-a-mole. Fluid in the lungs? Drain it. Blood sugar spike? Adjust insulin. Blood pressure swing? Tweak medications. Each intervention technically correct, but rarely connected to the larger question: Why is this happening to this person?

As James Scott observed in his study of systems, "Optimizing for single variables often leads to disaster." Our healthcare system has optimized for efficiency—quick diagnosis, standardized protocols, high patient throughput. Efficient for the hospital, bewildering for the family trying to understand what's happening.

The Realization

Every day at the hospital, I became more grateful I could be there for him. Not just for emotional support, but as Dad's wingman, tracking information, asking follow-up questions, connecting dots between conversations.

Dad is mentally well and aware about what's happening. But watching him try to process information from doctors while struggling to breathe, I realized how much cognitive load illness creates. He'd nod along with medical explanations, then look at me with confusion once the doctor left. The questions he wanted to ask would come to him hours later, long after the brief window of face-time had closed.

When medications are making him foggy, when the simple act of sitting up requires effort, that's not ideal condition to process complex medical decisions or remember which specialist said what about which medication. When you're sick enough to be hospitalized, you can't also be your own medical detective.

Learning the Role

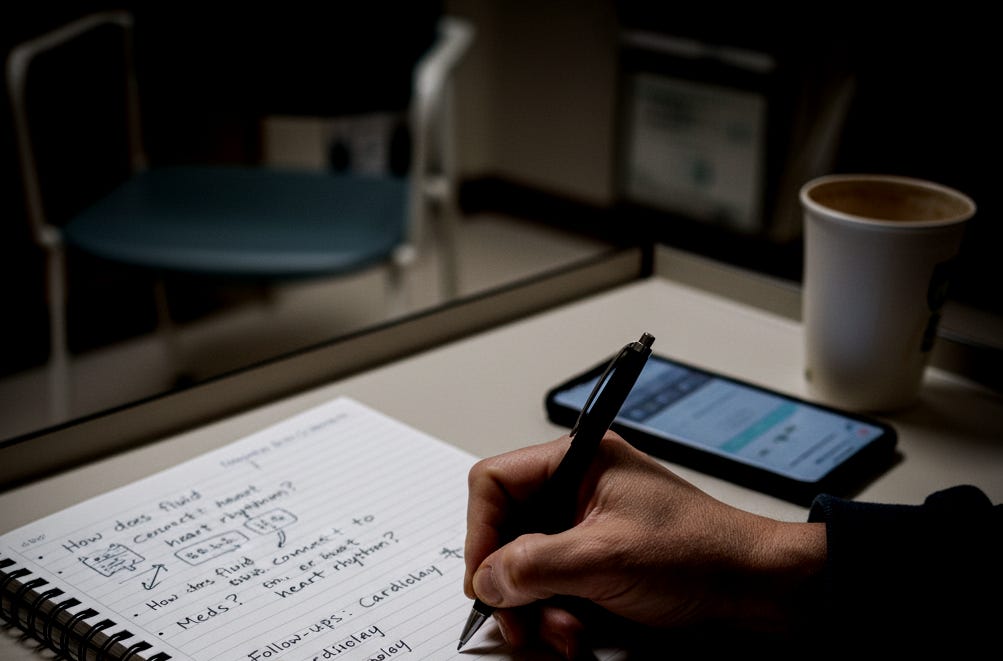

Settling into this role, I started carrying my phone like a reporter's notebook: How does the fluid connect to his heart rhythm? What's changed with his diabetes management? Which warning signs should terrify us at home?

I learned to lurk in hallways like some sort of medical paparazzi, strategically placing myself where doctors might pause long enough to explain what was actually happening. I became comfortable asking, "Can you help me understand how this connects to that?" I pushed—politely but persistently—for coordination between specialties. I never expected to become a full-time medical coordinator, but that's what Dad needed.

By day four, I understood the game. Dad wasn't a person with interconnected health issues. He was a heart case, a lung case, a diabetes case—each handled by different people who rarely talked to each other.

Hospital time operates on some parallel universe physics where five minutes of waiting feels like three hours, but eight days somehow blur into one endless Tuesday. Doctors round on their schedule, not yours. But being present during those brief windows was crucial, so I started writing down everything: medication changes, test results, discharge instructions.

The Memory of Better Care

The whole time, I couldn't stop thinking about how different this felt from when Mom was sick. Fifteen years ago, my mom faced her own health crisis. Local pulmonologists told her she'd likely need a lung transplant and would require oxygen for the rest of her life. Devastating news for a woman in her early sixties.

But we managed to get her into Mayo Clinic. Their approach was different from the start—not symptom-focused, but person-focused. Instead of applying standard protocols, they asked what this particular person needed. They took a comprehensive look at her medications, her lifestyle, her complete medical picture. Instead of accepting the local diagnosis, they asked deeper questions about root causes.

They adjusted her medications and treatment approach. No lung transplant. No oxygen. Fifteen years later, she's still doing well and living a life the way she want to live.

That experience profoundly shaped my expectations for what great healthcare looks like. When Mayo declined Dad's referral a few months ago, I was disappointed but not deterred. Now, with these new complications, we're trying again. Not because Mayo is magical, but because they represent something our traditional system often lacks: the willingness to look at the whole person rather than just the failing parts.

The Emotional Archaeology

The emotional reality of those days in the hospital were like working on an archaeological dig through my own anxiety. Each small piece of news becomes a fragment you examine for meaning. The chest X-ray showing improvement: hope rises. Blood sugar spikes despite careful monitoring: shoulders tense. One lung refuses to inflate after a procedure: fear floods in. The lung finally expands and holds: relief so profound it's almost blissful.

You realize how much of parental love is just waiting for the next result, the next update, the next sign that the person who taught you to ride a bike is going to be okay.

When Dad finally came home, I felt like I'd been holding my breath for eight days. We could all exhale a little. But vigilance remains. Daily weigh-ins to catch fluid build-up early. A complex schedule of follow-ups with cardiology, pulmonology, and endocrinology. The constant awareness that his body has crossed some invisible threshold where small symptoms demand immediate attention.

This is the reality of aging, for parents and children both. The gradual shift from taking health for granted to managing it actively, carefully, with the knowledge that the stakes keep rising.

The Deeper Questions

Sitting in that hospital room got me thinking about bigger questions. How do we age in a system designed for acute intervention rather than long-term wellness? How do we maintain human dignity in an environment optimized for efficiency? How do we balance the miracles of modern medicine with the fundamental need to be seen and understood as whole people?

The most profound moments during Dad's hospitalization were the small acts of seeing him as a person: the nurses who noticed he was cold and brought extra blankets without being asked, the assistants who took time to patiently help him do the daily morning hygiene, the night shift aide who chatted with him about his family when he couldn't sleep.

These interactions were a gentle reminder that healing happens not just through clinical interventions, but through the deeper connections that caring creates.

Moving Forward

Mayo still hasn't called back about Dad's referral. The specialists still rarely talk to each other. Hospital time will continue to operate on parallel universe physics. Nothing about the system has changed.

But now I carry the knowledge that the system doesn't automatically see the person - someone has to keep insisting he's there.

When I visit Dad at home, I still find myself watching his chest rise and fall. But he's not counting his breaths anymore, he's just breathing. His lungs work the way they should, and I can see the person the hospital almost lost sight of.

…it’s nuts that something as inportant as medical care has no quality standards…it should be like a great jazz club, if you wear sandles no entrance…

Amit I wish a full return to health for your dad. Given my current role as a caregiver I agree that our health system is maddening. Anyone who has a chronic disease will either need to spend the majority of their time managing it or use the help of a family member to do so. I pray that as a culture we will find a way to bring more humanity into the system. I think it would bring about better outcomes in addition to alleviating a lot of emotional overwhelm and confusion.